Miniature livers will fly aboard the International Space Station in an upcoming study of whether microgravity can encourage the growth of healthy tissue with an abundant blood supply.

It’s an effort that could potentially lead to personalized tissues and organs grown in space for use in transplant surgeries, scientists say. In the next two experiments, the researchers plan to test how well liver tissue grows in microgravity, as well as test new technology designed to keep this tissue alive but super-cooled for its return trip to Earth.

“My ultimate goal for these tissues, if they are doing what we imagine and hope they are able to do with microgravity, is to use these tissues for therapy,” he said. Dr. Tammy Changprofessor of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. The tissue can be transplanted to treat a variety of diseases and disorders of liver function, Chang told Live Science.

Growing tissue in laboratory dishes on Earth can be challenging, in part because gravity pulls cells into contact with the bottom of a plate or dish. Gravity also puts cells under shear stress because, to keep cells suspended as they grow, their vessels must be agitated. In nature, after all, organs emerge in a developing embryo as it floats in the amniotic fluid in the uterus, or in the fluid cushion provided by an egg.

These ever-present challenges with gravity have led researchers to develop rotating bioreactors that simulate a low-gravity environment by spinning very quickly. This allows miniature tissues and organs, or “organoids,” to be grown under artificial conditions, but these spinning vessels also put stress on the tissues, especially as the groups of cells inside them get larger.

Related: Scientists discover a new type of cell in the liver

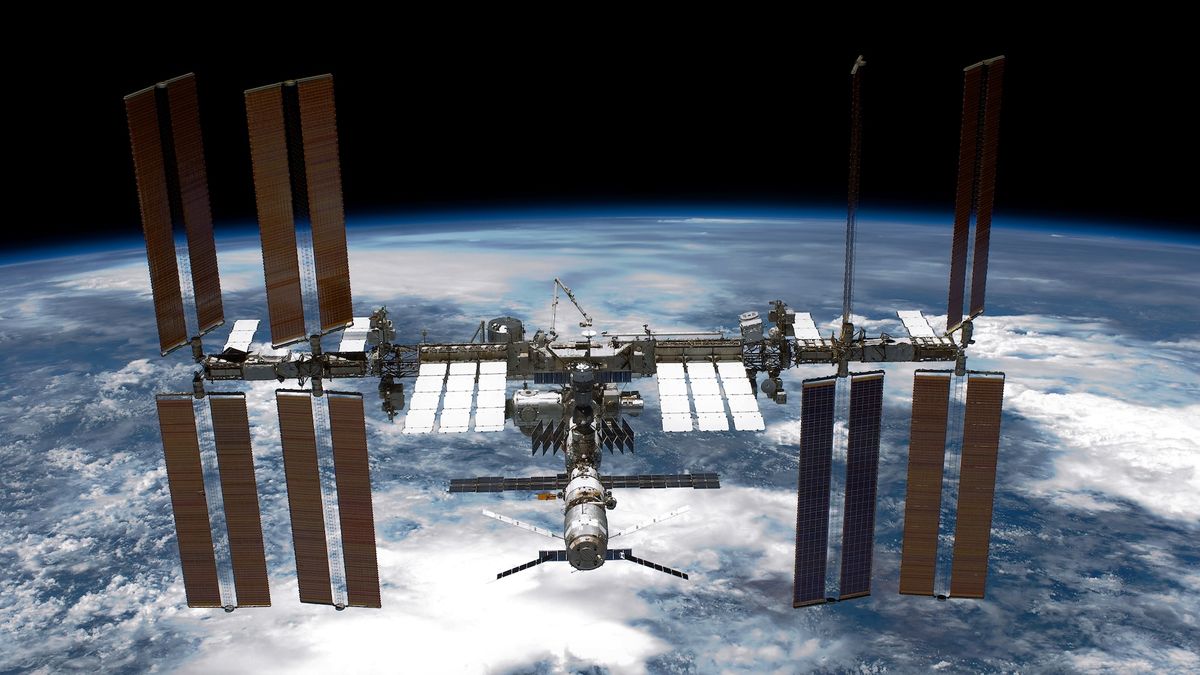

Chang and colleagues think that organoids can be best grown in a stable, high-quality microgravity environment like that found on the International Space Station.

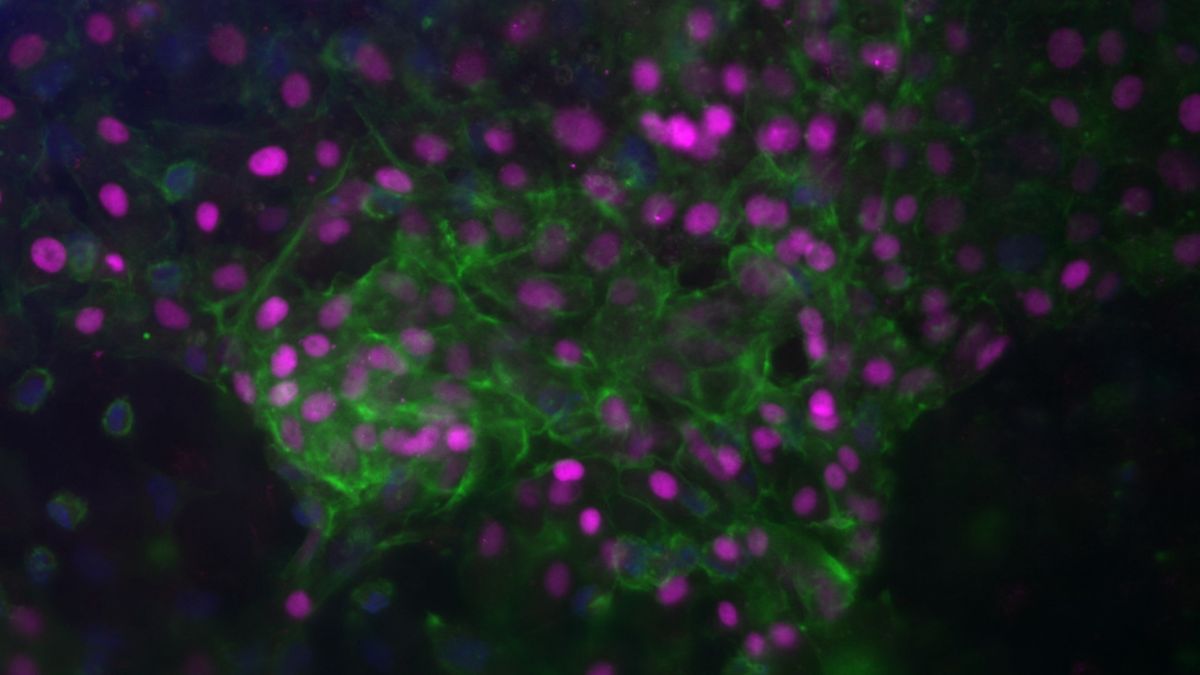

“These organoids are typically 200 microns in diameter, which is 0.2 millimeters. [0.008 inches]will be able to further organize and interact with each other to develop larger tissues and, in particular, tissues that are vascularized,” said Chang, who presented her research at the American College of 2024 surgeons in San Francisco on Tuesday (October) 22. vascularized tissues are filled with many blood vessels.

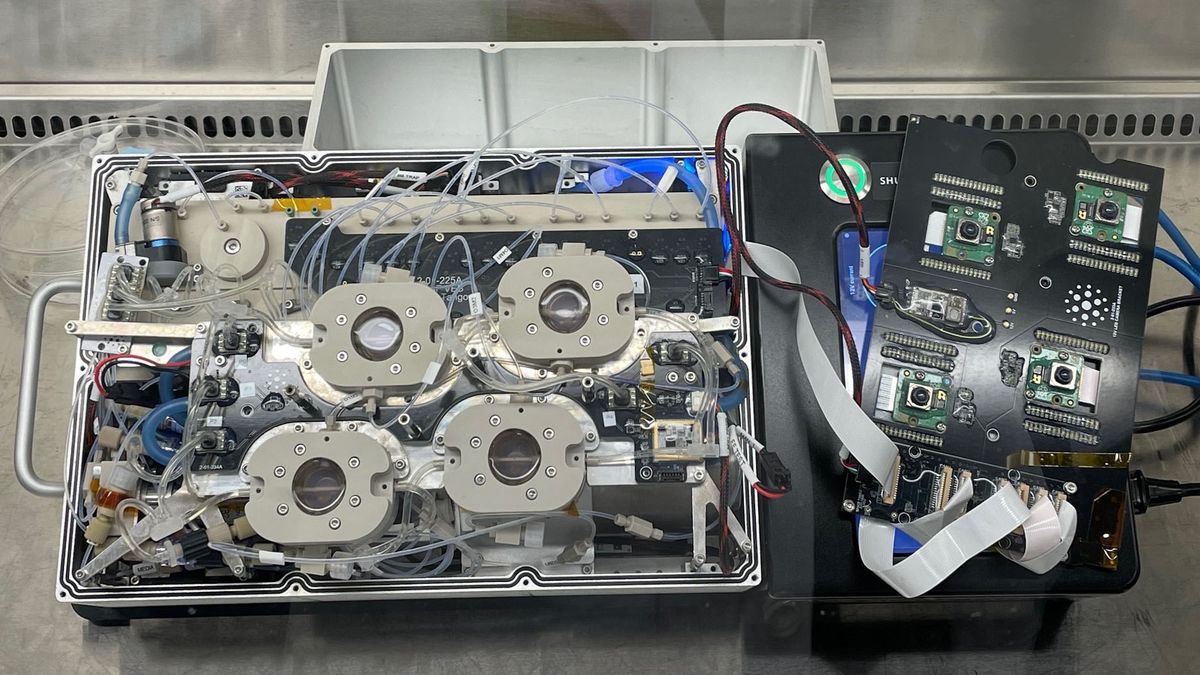

To grow their space-age liver organoids, Chang and her team use “induced pluripotent stem cells,” which are adult cells reprogrammed to be stem cells that can give rise to different types of tissue. The researchers then force these engineered stem cells to transform into liver cells and grow the cells in a special spherical bioreactor, called the Tissue Orb. This globular reactor has a central channel that mimics a blood vessel in its center. Feeding organoids with this type of circulatory system is the key to growing larger pieces of tissue.

“Our concept is that these organoids in the main chamber can fuse and interact with the central canal and develop a more complex and larger vascularized tissue,” Chang said.

The next liver tissue experiment will fly to the ISS in early 2025. The tissue will grow aboard the station for two weeks and then be fixed—placed in a preservation solution—for analysis back on Earth. A second experiment, likely to occur later in 2025 or early 2026, will test a supercooling system for returning living tissue to Earth.

These miniature livers are not the first organoids grown aboard the ISS. Researchers are using organoids grown in space to investigate the questions ranging from how the brain ages to how cancer develops and how it responds to drugs.

Flying an experiment to the space station is the culmination of years of work, Chang said: “It’s very exciting to have an experiment on board the ISS.”

Ever wonder why? some people build muscle more easily than others OR why spots appear in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works community@livescience.com with the title “Health Desk Q”, and you can see the answer to your question on the website!